My competence seems to cycle back and forth from leading-edge to generic.

I started as a specialist, with a PhD in robotics, head-hunted by the robotics department of the UK Nuclear industry.

A few years later, I was a technology manager delivering solutions to customers in the nuclear, aerospace, pharmaceutical, and financial industries. A generalist

Then, I was CEO. Raising finance, recruiting, designing departments, objectives, process, operations. The ultimate generalist

Then, as the dot-com bombed, I stopped having a job.

I joined 100,000 other business managers who were out of work.

That was the end of a cycle

You have a Choice

The choice of a specialist skill or a generic skill is hard.

The choice, like any investment, is a compromise between risk and reward.

For both people and companies. We either choose or it is chosen for us.

Often we dont seem to have a choice. It just happens

The Lure of Generic Skills

Learning excel or outlook are good investments. They are low risk choices, most likely to pay off

Lawyer, manager, accountant, salesman, marketing are also low risk choices.

Job boards always have openings for good managers and salesman.

A manager, salesman or accountant can work anywhere.

Business is about managing people. If you can manage people, you can manage any business.

Managing Human Capital, Harvard Business School

Generalist skills provide structure, certainty and choice. Established education, clear career path, wide choice of employers and customers.

It is the sensible, reputable choice.

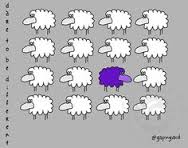

Why be different?

Global Markets: Commoditization of Skills

Globalization and technology have increased the supply of skills and services

Generic skills and services are the first to be replicated by competitors in different geographies.

In the world of Google, and online job search, your competition is just one click away

Being the best at a generic skill no longer guarantees a job.

You can no longer compete by simply being better

The Need to Be Different

To compete, you need a service and skills that are not replicated easily

I dont want to be the best. I want to be the only.

Your skills need to be special, different

If you are not different, you have no identity.

You’re just a commodity

To have an identity, you need a point of difference

And if you dont have one, you need to create one

Differentiation: You Have to Choose

Making yourself different involves choosing. You have to choose a focus. You have to choose your difference.

Persisting with your focus involves saying “no” to jobs, requests and clients outside of that focus

Acquiring a specialism, a differentiation requires a sacrifice. Requires an investment

The greater your focus, the greater the possible reward, the more risky the investment.

Increasingly, without risk, there is no reward. It is the nature of the current market.

You will have to take some risk.

Focus is the Hardest Thing

Most of us like being generalists.

I like being versatile. Give me a problem, I will fix it.

I dont have to make choices. I just serve.

I like diverse problems. I like learning new things.

Variety, is it not the smart thing?

No

Focus is the hardest thing.

Rules of Focus: The One Thing

Conclusion: How Your Company Values You

A company is as competitive as its differentiation in the market

Companies value the people that create the difference

All companies can hire generic skill staff. Therefore, that can’t provide the company’s differentiation.

The staff with skills specific to the company create the differential. They focus on the company’s specific domain, its context, its products.

“Computer science purists love the art of coding, if the algorithm is cool, if the integration is pretty, they’re happy.

For me, it’s all about the end product, not how I got there.”

Are you loyal to your products, or to your generic skill?

You can measure Domain Specific competence

How much do you know of the company’s specific context?

Do you know the customer? the product users? the specific technology? the product? the competition?

The highest scorer in Domain Specific competence is the company founder, always

If you score high on Domain Specific competence, you make a difference

If you want to make a difference, dont be generic

References:

– College and Business Will Never Be The Same – End of Silo’d Careers, Steve Blank

– Knocking Down Walls, Marty Cagan

– The Internal Agency Model, Marty Cagan

– The Refragmentation, the demise of the corporate class, and rise of creative classes, Paul Graham

– How Google Works, Eric Schmidt, Jonathan Rosenberg

– Developing Strong Product Owners, Marty Cagan

– The Role of Domain Experience, Marty Cagan

– Product vs IT Mindset, Marty Cagan

– Finding Your Edge, Alice Bentinck, Entrepreneur First

– So You Want to Manager?, Julie Zhuo, Facebook

– The Zag, Marty Neumeier

– The Brand Flip, Marty Neumeier

– The Linchpin, Seth Godin

– Theory of Efficient Markets, where return is proportionate to risk

– The no.1 Reason to Focus, Seth Godin

– No is Essential, Seth Godin

– Reductio Ad Absurdum – The One Thing, Dave Trott

– “T-Shaped People”, Tim Brown, IDEO

– Understanding UX Skills, Irene Au

– Advice for Thriving in a World of Change, Joi Ito